Chapter_01: Introduction.

Copyright (c) 2022 Mahmoud Harmouch

Reset your brain.

Don’t try to memorize everything because you don’t have to, just remember that something exists to know what you are looking for.

Theory without Practice is useless; Practice without Theory is blind.

Practice/coding is the key to success as a programmer.

Don’t give up. Difficult roads often lead to beautiful destinations.

Table Of Content (TOC).

- A Tutorial Introduction

1.1 What is Python ?

1.2 Why Python ?

1.3 Interpreted Language - Running Python

- Python Syntax

3.1 Print Instruction

3.2 Comments

3.3 Variables

3.3.1 Names

3.4 literals

3.4.1 String Literals

3.4.1.1 String Formatting

3.4.1.2 Special characters

3.4.1.3 More Strings Examples

3.4.1.4 Useful Strings Functions

3.4.1.5 More Strings Methods Examples

3.4.2 Numeric literals

3.5 Sequences

3.5.1 Immutable Sequences

3.5.1.1 Strings

3.5.1.2 Tuples

3.5.1.3 Bytes

3.5.1.4 Frozenset

3.5.2 Mutable Sequences

3.5.2.1 Lists

3.5.2.2 Bytearray

3.5.2.3 Set

3.5.2.4 Array

3.5.2.5 Dictionary

3.5.3 Sequences Exercices

3.6 Conditional Statements

3.6.1 If Statement

3.6.2 If-Else Statements

3.6.3 If-Elif Statements

3.6.4 Nested If-Else Statements

3.6.5 Exercices

3.7 Loops

3.7.1 While loop

3.7.2 For loop

3.7.3 Loop Else

3.8 Operations.

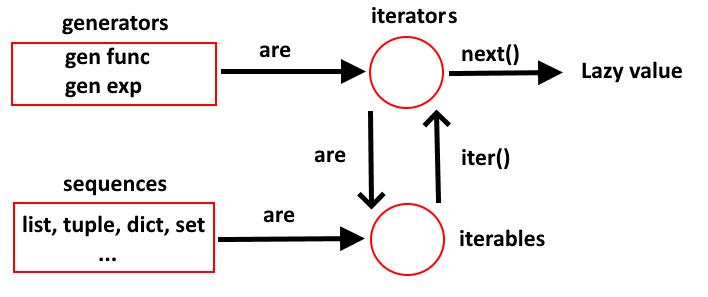

3.9 Iterables.

3.10 List Comprehensions

3.11 Generators

3.11.1 Generator Function

3.11.2 Generator Expression

3.11.3 Generator Exercises.

3.12 Input

3.13 Exceptions

1. A Tutorial Introduction

The goal of this chapter is to get you familiar with python 3 and its essential features.

1.1 What is Python ?

Python is a high-level, general-purpose, programming language that has the following features:

- It is designed to produce high quality, human-readable and maintainable code;

- Portable: Python is a cross-platform programming language, it can be used on Linux, Windows, macOS…;

- Easy to integrate code;

- Object-Oriented programming language;

- Completely Free;

- Highly Productive: A program written in Python is typically 2 to 4 times shorter than an equivalent C++ program;

- Dynamic: the source code is not compiled unlike other languages like C, C++, java, but executed on the fly. It is called an interpreted language;

1.2 Why Python ?

Go To TOC.

Python is a good programming language to start with for a beginner who doesn’t know programming at first. Python is very powerful and it is used in a lot of domains. The following list describes the different areas in which Python is mostly used:

- System Administration: System administrators often need to design small programs to automate certain tasks. Therefore the usage of python because it is simpler and more direct;

- Rapid Prototyping: There are a lot of softwares powered by python that allows you to build graphical user interfaces which can be useful for performing specification cycles between clients and the development team. Qt designer is a good example of that;

- Scientific Research: Python is much easier to learn for a researcher who does not have the knowledge of programming. Memory management, the use of pointers, the typing of variables, and all the details of the implementation of a program are all constraints that are far away from the first concerns of a researcher;

- Web Applications: A lot of web frameworks, written in Python(e.g. Twisted, Django …) are very popular and active which allows python to the forefront of the scene in web development.

1.3 Interpreted Language.

Go To TOC.

Python commands and instructions are executed by the interpreter, which is written in C language and has different implementations like :

- CPython: C implementation, which is the default implementation of Python;

- Jython: Java implementation, which allows you to run Python source code in a Java environment, and use Java modules in Python code transparently;

- PyPy: Python implementation of the Python language;

- IronPython: implementation for .NET and Mono;

- Stackless Python: a variant of CPython, slightly faster.

Note that the major drawback of Python is that it is a dynamically typed language(not statically typed). This means that the interpreter doesn’t check for variables types before runtime. this can lead to slowing down the speed of execution of the code while checking the type of the variables during runtime since there is no compile stage before runtime. So Python is very slow compared to other statically typed languages like Java, C#, C…

2.. Running Python.

Go To TOC.

You can run the interpreter by simply entering the ‘Python3’ command in your terminal :

~$ python3

Python 3.7.6 (default, Jan 8 2020, 19:59:22)

[GCC 7.3.0] :: Anaconda, Inc. on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

As you can see, the interpreter displays its python version, the compiler version and the copyright message and it is listening for statements from the user.

One of the most useful features in python is the interaction mode(shell), which allows the user to do operations and see results immediately on the shell.

>>> 699120 + 20958 - 1932

718146

>>> _

718146

The _ variable in python holds the result of the previous operation. you could run your own program(script) in a file and name it with the extension ‘.py’ and execute it on the shell without the usage of interactive mode.

# hi.py

print('Hi There!')

~$ python3 hi.py

Hi There!

In a Linux distro, you can add at the first line of your program the following line to make the file executable on the shell :

#!/usr/bin/env python3 # must be at the first line or you'll get a syntax error

# hi.py

print('Hi There!')

To make it executable, just give the user the execution privileges using the following

~$ chmod u+x hi,py

Now you can run the executable file like the following:

~$ ./hi.py

Hi There!

Back to the interpreter, you can exit it by pressing Ctrl + D which signal the interpreter an end of the file command, or by raizing a system exit exception as follows:

>>> raise SystemExit()

~$

you can also use the exit() method to exit the interactive prompt, aka the Read Eval Print Loop (REPL).

3. Language Syntax.

Go To TOC.

A complete documentation on Lexical analysis can be found on Python Docs.

3.1 Print Instruction.

Go To TOC.

>>> print("Hi There!")

Hi There!

>>> print(5)

5

>>> print(4 * 4)

16

>>> print(109 + 15 + 100)

224

>>> print("text goes here!")

text goes here!

>>> print(("text", "goes", "here!"))

('text', 'goes', 'here!')

>>> print(text goes here!)

File "<stdin>", line 1

print(text goes here!)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>> print(3,4,6,"a",'b')

3 4 6 a b

>>> print(3,4,6,"a",'b', sep = " ") # By default, print uses a whitespace as a seperator.

3 4 6 a b

>>> print(3,4,6,"a",'b', sep = " ", end = "\n") # By default, print uses \n to mark as the end of line.

3 4 6 a b

>>> print(3,4,6,"a",'b', sep = " ", end = "<<\n")

3 4 6 a b<<

>>> print(3,4,6,"a",'b', sep = ":", end = "<<\n")

3:4:6:a:b<<

>>> print(3,4,6,"a",'b', sep = ":", end = None) # By default, same behavior as end = "\n"

3:4:6:a:b

>>> import sys

>>> print(sys.version)

3.7.6 (default, Jan 8 2020, 19:59:22)

[GCC 7.3.0]

>>> print(sys.version_info)

sys.version_info(major=3, minor=7, micro=6, releaselevel='final', serial=0)

>>>

3.2 Comments.

Go To TOC.

In Python, you can use the hash sign (#) to place comments on a single line.

# first comment

print ("Hi There!") # second comment on the same line of the statement.

# third comment

# fourth one is the best

These comments are ignored by the interpreter which considers, in this case, the ) symbol as the end of the print statement, except when it is linked to the next line by the backslash character \ as the following example shows:

>>> print("text goes \

... here!")

text goes here!

>>> print("text goes \ # you can't insert a comment here!!!!!

File "<stdin>", line 1 ^

SyntaxError: EOL while scanning string literal

3.3 Variables.

Go To TOC.

Python’s Variables are object-based. Each object has :

-

An Identifier: It is a positive unique integer that is created once for all when the object is being created. It is calculated from the object’s memory address.

-

A Type: The type of the object is immutable. you cannot change it during the runtime.

-

A Value: The value assigned to the object can be modified depending on the type of the object. For instance, string and tuple type objects cannot be modified after their creation. They are called immutable objects.

-

Attributes: properties of the object.

-

Name: an object must have a name.

-

One or more base classes : for exemple an object of type int has the ‘object class’ as base class(parent class).

The following callable objects allow you reading each of the attributes described:

-

id (): returns the identifier of an object;

-

type (): returns the type of an object;

-

dir (): lists all the features of an object.

So as it is said before, Everything in python, at the runtime, is an object.

>>> 32, id(32), type(32)

(32, 94140309858016, '<class 'int'>')

>>> 32, id(32), type(32)

(32, 94140309858016, '<class 'int'>')

>>> 32, id(32), type(32)

(32, 94140309858016, '<class 'int'>')

Every object has a value(32 here), an id which is used to indicate where it is stored in memory(94140309858016) and a data type(integer).

It is not convenient to use the identifier(id) as a name for the 32 value, Hence the need for assignments.

An assignment is made using the = symbol, like this:

>>> a = 32

>>> a,id(a),type(a)

(32, 94140309858016, '<class 'int'>')

Notice that the object name a has the same reference of object 32(id = 94140309858016).

The object name a has the following attributes :

>>> dir(a)

['__abs__', '__add__', '__and__', '__bool__', '__ceil__', '__class__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__divmod__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__float__', '__floor__', '__floordiv__', '__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getnewargs__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__index__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__int__', '__invert__', '__le__', '__lshift__', '__lt__', '__mod__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__neg__', '__new__', '__or__', '__pos__', '__pow__', '__radd__', '__rand__', '__rdivmod__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__rfloordiv__', '__rlshift__', '__rmod__', '__rmul__', '__ror__', '__round__', '__rpow__', '__rrshift__', '__rshift__', '__rsub__', '__rtruediv__', '__rxor__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__sub__', '__subclasshook__', '__truediv__', '__trunc__', '__xor__', 'bit_length', 'conjugate', 'denominator', 'from_bytes', 'imag', 'numerator', 'real', 'to_bytes']

>>> a.__str__()

'32'

Notice that the private (__) attribute ‘str’ hold the value of a as string.

Let’s take the following example :

>>> b = a * 3

>>> b,id(b),type(b)

(96, 94140309860064, '<class 'int'>')

>>> a,id(a),type(a)

(32, 94140309858016, '<class 'int'>')

the interpreter takes the expression at the right side of the assignment symbol = and evaluates it. As a result, an object of type integer whose value is 96 is created and stored in memory and the reference of that object is assigned to b. Note that, the value of this particular object is already stored in memory.

>>> 96,id(96),type(96)

(96, 94140309860064, '<class 'int'>')

I think, in this particular example, the Python interpreter didn’t create a new object of value 96 in memory(because it is already stored at that id for optimization porpuses), it changes the reference of b only. This is only true because 32 is between -5 and 256.

From python C-API documentation, I found the following explanation:

The current implementation keeps an array of integer objects for all integers between -5 and 256, when you create an int in that range you actually just get back a reference to the existing object. So it should be possible to change the value of 1. I suspect the behavior of Python, in this case, is undefined. :-)

let’s try it for a number larger than 256 :

>>> b = 257

>>> id(b)

140086582008304

>>> id(257)

140086582008272

So as you can see, b and 257 are different objects in memory. Now lets create a variable and increment it and see how much it takes space in memory:

>>> a = 0

>>> a += 1

>>> a,id(a),type(a)

(1, 94140309857024, '<class 'int'>')

>>> a += 1

>>> a,id(a),type(a)

(2, 94140309857056, '<class 'int'>')

>>> a += 1

>>> a,id(a),type(a)

(3, 94140309857088, '<class 'int'>')

The id increments by 32(i found some cases on the internet where the id has increased by 16, maybe because it was a 32-bit architecture), my computer is 64 bits address space, so i think each object in python is stored on 32 bytes if you have a 64 bit machine.

you can assign one object to several variables simultaneously.

>>> a = b = 8

>>> id(a),id(b)

(94232164422624, 94232164422624)

Notice that a and b point to the same object address in memory.

you could assign multiple values to multiple variables at the same time.

>>> a, b = 32, 64

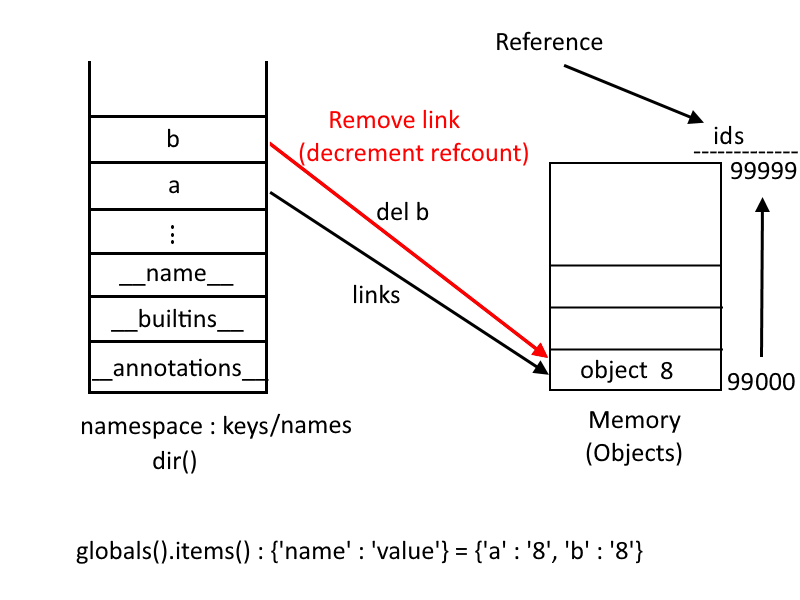

In python, objects are destroyed automatically(not explicitly) from memory by the garbage collector, which keeps a reference counter for each object. This field is incremented by one if other objects reference a given object. An example where this variable increases :

- assignment operator

- passing arguments

- inserting a new object into the list (the number of links for the object increases)

- a constructor like foo = bar (foo starts referring to the same object as bar) If this referencing(link) is destroyed, then the reference counter will decrease by one. If the reference counter reaches 0, then the interpreter starts the mechanism of destroying the object.

The reference counter of global variables never drops to zero.

>>> a = 8

>>> sys.getrefcount(a)

2

>>> b = a

>>> sys.getrefcount(a)

3

>>> del b

>>> sys.getrefcount(a)

2

3.3.1 Names.

Go To TOC.

Names are attached, as we saw previously, to objects. The following method shows the names that are stored in the namespace:

>>> dir()

['__annotations__', '__builtins__', '__doc__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__']

When you create a new object and give it a name, this name is stored in the namespace:

>>> a = 16

>>> dir()

['__annotations__', '__builtins__', '__doc__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'a']

You can write a function that returns an object’s name and value pair stored in the namespace as a dictionary:

>>> def names_values():

... obj = []

... for (name,value) in globals().items():

... if not name[:2] == '__':

... obj.append((name,value))

... return dict(obj)

...

globals().items() returns a tuple of names and values. dir() returns only the name(key)

>>> names_values()

{}

>>> a = 8

>>> b = 16

>>> c = a

>>> names_values()

{'a': 8, 'b': 16, 'c': 8}

>>> del c

>>> names_values()

{'a': 8, 'b': 16}

So it is all about storing and deleting names from the namespace. As it is said previously, the object will be destroyed from memory if the refcount reaches zero. So the object 8 won’t be destroyed because it is also referenced by the name a.

3.4 Literals.

Go To TOC.

A complete documentation on Literals can be found on Python Docs.

A literal in python is the simplest way to create an object, but at the same time it can be a constant, but which does not mean objects. A variable is assigned at the runtime, whereas a literal is assigned at the compile time.

>>> 1 # numeric literal

1

>>> "here goes a string" # string literal

'here goes a string'

>>> [1,2,3] # list literals

[1, 2, 3]

>>> {'k0':1,'k1':2, 'k3':3} # dict literal

{'k0': 1, 'k1': 2, 'k3': 3}

But this is not useful if you want to manipulate these values without assigning it to a variable. Hence the need for the assignment.

>>> a = 8

Here the object whose name is ‘a’ is created by the numerical literal 8. So, on the left side, we have the variable name and on the right, we have the literal. To see the difference between the built-in functions and the literals, you can create a list in two different ways :

>>> a = list([1,2,3]) # creating a list using a built-in function

>>> a = [1,2,3] # creating a list using a list literal

3.4.1 String Literals.

Go To TOC.

Strings are alphanumeric(text constant) values surrounded by quotes. Single or double quotes, or even three single or double-quotes.

>>> print("here we have a one-line string with one double quote")

here we have a one-line string with one double quote

>>> print('here we have a one-line string with one single quotes')

here we have a one-line string with one single quote

>>> print("""here we have multiple lines

... string with three double quotes""")

here we have multiple lines

string with three double quotes

>>> print('''here we have multiple lines

... string with three single quotes''')

here we have multiple lines

string with three single quotes

It is also possible to prefix strings with a character:

- r or R : “raw string” :used with regular expressions and with strings that contain backslashs :

>>> print('D:\files\file1')

D:

iles

ile1

>>> print(r'D:\files\file1')

D:\files\file1

It seems like\f act as a new line with tabulation: \n\t, in other terms a vertical tabulation.

- u or U : to indicate a Unicode string. Python 3 adopts the base Unicode standard, and the u prefix disappears.

>>> unicode = u'i am a unicode string'

>>> unicode

'i am a unicode string'

>>> type(unicode)

<class 'str'>

- b or B: to indicate a byte string. Each byte in a byte string corresponds to a certain value in the range of [0; 255].

>>> b'hi there'

b'hi there'

>>> b'hi there'[3]

116

Encoding and decoding methods make it possible to convert from type str to type bytes, using a correspondence table, called codec and having a unique name(UTF-8 is used in the example).

>>> string = 'this is string'

>>> byte_string = string.encode('UTF-8') # from str to bytes

>>> byte_string

b'this is string'

>>> decoded_string = byte_string.decode('UTF-8') # # from bytes to str

>>> decoded_string

'this is a string'

- f or F: this prefix has been added since python 3.6 which allows you to define a string as formatted. So using this prefix, you can add a placeholder for a certain variable with the help of curly braces

{}to indicate the appearance of this variable(e.g. precision of a number to display).

>>> from math import cos, pi

>>> print(f'Value of PI with 4 digit precision: {pi:+1.4}')

Value of PI with 4 digit precision: +3.1416

>>> for i in range(1,20):

... x = cos(pi/i)

... print(f'|i = {i:<2}| cos(pi/{i:<2}) = {round(x,2):<+5.2}|')

... # < indicates left alignement; ^ for center alignment; > for right alignment;

... # the number after the synbol < indicate the width of the column to display

... | | | | | |

... |..| |..| |.....|

|i = 1 | cos(pi/1 ) = -1.0 |

|i = 2 | cos(pi/2 ) = +0.0 |

|i = 3 | cos(pi/3 ) = +0.5 |

|i = 4 | cos(pi/4 ) = +0.71|

|i = 5 | cos(pi/5 ) = +0.81|

|i = 6 | cos(pi/6 ) = +0.87|

|i = 7 | cos(pi/7 ) = +0.9 |

|i = 8 | cos(pi/8 ) = +0.92|

|i = 9 | cos(pi/9 ) = +0.94|

|i = 10| cos(pi/10) = +0.95|

|i = 11| cos(pi/11) = +0.96|

|i = 12| cos(pi/12) = +0.97|

|i = 13| cos(pi/13) = +0.97|

|i = 14| cos(pi/14) = +0.97|

|i = 15| cos(pi/15) = +0.98|

|i = 16| cos(pi/16) = +0.98|

|i = 17| cos(pi/17) = +0.98|

|i = 18| cos(pi/18) = +0.98|

|i = 19| cos(pi/19) = +0.99|

So as you can see, the f prefix is so much handy and useful. Alignment is done using one of the following characters:

| align | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

< |

align the object to the left. | >>> print(f"[{'left':<16}]")[left ] >>> print(f"[{'left':<<16}]")[left««««««] |

> |

align the object to the right. | >>> print(f"[{'right':>16}]")[ right] >>> print(f"[{'right':>>16}]")[»»»»»>right] |

^ |

align the object to the center. | >>> print(f"[{'center':^16}]")[ center ] print(f" | {'center':^^16}]")[^^^^^center^^^^^] |

= |

forces the padding to be placed after the sign (+ or -) but before the digits. |

>>> print(f"[{+32:0=+5}]")[+0032] >>> print(f"[{+32:^=+10}]")[+^^^^^^^32] |

The sign option is used only for numbers with the following values:

| sign | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

+ |

- for negative numbers and + for positive numbers. |

>>> print(f"[{+32:^+5}]")[ +32 ] >>> print(f"[{-32:^+5}]")[ -32 ] |

- |

- for negative numbers and nothing for positive numbers. |

>>> print(f"[{+32:^-5}]")[ 32 ] |

Space |

- for negative numbers and whitespace for positive numbers. |

>>> print(f"[{+32:^ 5}]")[ 32 ] |

the general form of f strings is the following:

{variable : fill_padding align sign column_width .precision type}

>>> print(f"{-32.215663:*^+15.2f}")

****-32.22*****

3.4.1.1 String Formatting.

Go To TOC.

There are three methods in python that can be used to format strings:

- Using the

%modulo sign(borrowed from c language) with one of the following values:

| %type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

%d,%i,%u |

signed decimal, signed integer and unsigned decimal. | >>> print("%d + %i = %u"%(10,15,10+15))10 + 15 = 25 |

%o |

unsigned octal | >>> print(f"oct: %o"%41) oct: 51 |

%x or %X |

hexadecimal value, prefixed by 0x or 0X. | >>> print(f"hex: %x %X"%(0x12,0X32))hex: 12 32 |

%e or %E |

scientific notation of a number with a presicion of 6.(‘e’ pr ‘E’ as exponent) | >>>print('%E %e pounds' %(212345,212345))2.123450E+05 2.123450e+05 pounds |

%f or %F |

fixed-point notation with a presicion of 6. | >>>print('%f %F pounds' %(21.2345,21.2345))21.234500 21.234500 pounds |

%g or %G |

for floating point values, equivalent to %e or %E if the exponent is greater than -4 or less than precision, otherwise equivalent to %f. | >>> print('%g %G pounds' %(234512312,00000.21000312))2.34512e+08 0.210003 pounds |

%c |

converts the integer to the corresponding unicode character. | >>> print('%c is a char' %(123)){ is a char |

%r |

return the value of the attribute __repr__ |

>>> a = 10>>>a.__repr__()‘10’ >>> print("the value of a.__repr__() is %r"%a)the value of a.repr() is 10 |

%s |

return the value of the attribute __str__ |

>>> a.__str__()‘10’ >>> print("the value of a.__str__() is %s"%a)the value of a.str() is 10 |

%% |

insert the % sign. | >>> print("score is %g %%"%95.1)score is 95.1 % |

%(key)s |

insert the value of the key in the dictionnary. | >>> print('%(key1)s %(key2)s %(key3)s'%{'key1':'value1','key2':'value2','key3':'value3'})value1 value2 value3 |

- using the format method(borrowed from C# language) like the following examples :

>>> '{0}, {1}, {2}'.format('1', '2', '3')

'1, 2, 3'

>>> '{}, {}, {}'.format('1', '2', '3')

'1, 2, 3'

>>> '{2}, {1}, {0}'.format('1', '2', '3')

'3, 2, 1'

>>> '{2}, {1}, {0}'.format(*'123') # unpacking argument sequence

'3, 2, 1'

>>> '{0}, {0}, {0}'.format('1', '2', '3') # arguments' indices can be repeated

'1, 1, 1'

- using the

fprefix as the previous section explains. for more information about string formatting, you can read python documentation.

3.4.1.2 Special characters.

Go To TOC.

Python allows you to insert special characters in a string literal. the following table contains a list of spetial characters:

| \Character | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

\', \" |

insert a single or double quote in a string literal. | >>> print("python\'s notes") python’s notes |

\n |

insert a new line | >>> print("that's\nnice!")that’s nice! |

\r\n, \r |

insert a new line in windows, \r on Mac, end of line character(EOL). | >>> print("that's\r\nnice!")that’s nice! |

\\ |

insert a single backslash in a string literal. | >>> print("The file is in D:\\files\\file1")The file is in D:\files\file1 |

\v |

insert a vertical tabulation. | >>> print("This is a vertical\v tabulation")This is a vertical tabulation |

\t |

insert a Horizontal tabulation(tab). | >>> print("This is a horizontal\t tabulation")This is a horizontal tabulation |

\b |

erase/delete a previous character from a string literal. | >>> print("the last letter will be erased\bd")the last letter will be erased |

\Oct |

insert an octal value of a character. | >>> print("\110i There!")Hi There!` |

\xHx |

insert an hexadecimal value of a character. | >>> print("\x48i There!")`Hi There! |

\N{noun} |

insert a charater defined by a noun. | >>> print('\N{dollar sign}')$ >>> print('\N{pound sign}')£ |

Please refer to this link if you want to search for ASCII characters or simply type man ascii in your terminal.

3.4.1.3 More Strings Examples.

Go To TOC.

>>> a = 'Python is cool' # String type.

>>> b = r'Python is cool' # raw String.

>>> a == b # both strings have the same value.

True

>>> a is b # but they are not the same object.

False

>>> id(a),id(b)

(140092435297776, 140092435297904) # each string points to a different object in memory.

>>> a = 'Python\t is cool'

>>> a = 'Python\tis cool'

>>> b = r'Python\tis cool'

>>> a,type(a),id(a)

('Python\tis cool', <class 'str'>, 140092435297776)

>>> b,type(b),id(b)

('Python\\tis cool', <class 'str'>, 140092435297840)

Both objects share the same type str but different values and references.

>>> a is b

False

>>> a == b

False

>>> a = r'£'

>>> b = '\u00A3'

>>> c = '\N{pound sign}'

>>> a == b == c

True

>>> a is b is c

True

>>> id(a),id(b),id(c)

(140578043342896, 140578043342896, 140578043342896) # a, b and c are the same object in memory .

>>> a,b,c

('£', '£', '£') # Same Value.

>>> a = '512512'

>>> b = a.encode(encoding = 'ascii') # create a new object in memory.

>>> b

b'512512'

>>> c = b.decode(encoding = 'ascii') # create another new object in memory and not reference a !!!

>>> c

'512512'

>>> a == c # same value.

True

>>> a is c # different objects.

False

>>> a = int(a) # create a new object in memory.

>>> c = int(c) # create another new object in memory.

>>> a is c # same type and value but different objects.

False

Exception for numbers between -5 and 256 as it said before.

>>> a = '128'

>>> b = a.encode(encoding = 'ascii')

>>> c = b.decode(encoding = 'ascii')

>>> a is c

False

>>> c = int(c)

>>> a = int(a)

>>> a is c # because it is between -5 and 256.

True

3.4.1.4 Useful Strings Functions.

Go To TOC.

For a complete list of string methods, you can refer topython docs.

| Function | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

len(s) |

return the number of element in s. |

>>> s = 'this is a string'>>> len(s)16 |

min(s) |

return the minimum value in s. |

>>> [ord(char) for char in s][116, 104, 105, 115, 32, 105, 115, 32, 97, 32, 115, 116, 114, 105, 110, 103] >>> min(s)‘ ‘ >>> ord(min(s))32 |

max(s) |

return the maximum value in s. |

>>> max(s)‘t’ >>> ord(max(s))116 |

sorted(s) |

sort values from lowest to highest. | >>> sorted(s)[’ ‘, ‘ ‘, ‘ ‘, ‘a’, ‘g’, ‘h’, ‘i’, ‘i’, ‘i’, ‘n’, ‘r’, ‘s’, ‘s’, ‘s’, ‘t’, ‘t’] |

list(reversed(s)) or list(s[::-1]) |

reverse the order of the values in the string(index 0 becomes index -1…) | >>> list(reversed(s))[‘g’, ‘n’, ‘i’, ‘r’, ‘t’, ‘s’, ‘ ‘, ‘a’, ‘ ‘, ‘s’, ‘i’, ‘ ‘, ‘s’, ‘i’, ‘h’, ‘t’] >>>s[::-1]‘gnirts a si siht’ >>> list(s[::-1])[‘g’, ‘n’, ‘i’, ‘r’, ‘t’, ‘s’, ‘ ‘, ‘a’, ‘ ‘, ‘s’, ‘i’, ‘ ‘, ‘s’, ‘i’, ‘h’, ‘t’] |

s.startswith('str') |

return True only if s starts with str, otherwise it return False |

>>> s‘this is a string’ >>> s.startswith('h')False >>> s.startswith('t')True >>> s.startswith('th')True >>> s.startswith('this')True |

s.endswith('str') |

return True only if s ends with str, otherwise it return False |

>>> s.endswith('ng')True >>> s.endswith('gn')False |

s.upper() |

converts a string to uppercase. | >>> s.upper()‘THIS IS A STRING’ |

s.lower() |

converts a string to lowercase. | >>> s.lower()‘this is a string’ |

s.strip() |

removes whitespaces from start and end of the string s. |

>>> s = ' Remove start and end whitespaces '’ >>> s‘‘ Remove start and end whitespaces ‘ >>> s.strip()‘Remove start and end whitespaces’ |

s.lstrip() or s.rstrip() |

removes whitespaces from start or from end of the string s, respectively. |

>>> s.lstrip()‘Remove start whitespaces ‘ >>> s.rstrip()‘ Remove end whitespaces’ |

s.find('str', start_index) |

return first from left occurrence index of str in s starting from index start_index if found, otherwise return -1 |

>>> s = 'python is so cool'>>> s.find('o',5)11 |

s.index('str', start_index) |

same as find except it will throw a ValueError exception if str is not in s |

>>> s.find('1',5)-1 >>> s.index('1')Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>ValueError : substring not found |

s.count('str', start_index) |

count the occurrence of str in s starting from start_index. |

>>> s.count(' ',7)2 |

3.4.1.5 More Strings Methods Examples.

Go To TOC.

>>> s = 'string'

>>> sorted(s)

['g', 'i', 'n', 'r', 's', 't'] # lowest to highest sorting.

>>> sorted(s, reverse = True)

['t', 's', 'r', 'n', 'i', 'g'] # highest to lowest sorting.

>>> list(reversed(s))

['g', 'n', 'i', 'r', 't', 's'] # reverse ordering of the string.

>>> s.upper()

'STRING'

>>> s.lower()

'string'

>>> s.title()

'String'

>>> s.istitle()

False

>>> s.title().swapcase()

'sTRING'

>>> 'st' in s

True

>>> s += s

>>> s

'stringstring'

>>> s.find('i')

3

>>> s.find('i',5)

9

>>> s.find('i',s.find('i') + 1)

9

>>> s.index('i',s.index('i')+1)

9

>>> s.index('1')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: substring not found

>>> s.find('1')

-1

>>> s.count('i')

2

3.4.2 Numeric literals.

Go To TOC.

There are four types of numeric literals to represent values:

- Integers : reserved for a variable whose value is a stored relative integer in exact value. The possible values for such a variable are only limited by the capabilities of the computer;

>>> 10**1024 + 1 # no limit for integers in python!

100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001

let’s examine how python stores this insane number into memory. To do so, the sys module provides us a helpful attribute:

>>> for element in dir(sys):

... if 'int' in element.lower():

... print(element)

...

__breakpointhook__

__interactivehook__

breakpointhook

getcheckinterval

getswitchinterval

int_info # this attribute gives us the information about integers;

intern

setcheckinterval

setswitchinterval

>>> sys.int_info

sys.int_info(bits_per_digit=30, sizeof_digit=4)

So in python, there is a custom method to store integers larger than 230; the interpreter takes that number and divide it into a sequence of digits written in base 230 numerical system and store the result in a 4 bytes array.

23479521057823154763809

>>> divmod(23479521057823154763809, 2**30) #return a tuple of form (quotient,Remainder)

(21867008002310, 219150369)

>>> divmod(21867008002310, 2**30)

(20365, 255756550)

#stop here because the quotient is less than 2**30 (0 <= ob_digit[i] <= MASK =2**30)

From C-Python repo, you can find the following explanation on the representation of long integer:

/* Long integer representation.

The absolute value of a number is equal to

SUM(for i=0 through abs(ob_size)-1) ob_digit[i] * 2**(SHIFT*i)

Negative numbers are represented with ob_size < 0;

zero is represented by ob_size == 0.

In a normalized number, ob_digit[abs(ob_size)-1] (the most significant

digit) is never zero. Also, in all cases, for all valid i,

0 <= ob_digit[i] <= MASK.

The allocation function takes care of allocating extra memory

so that ob_digit[0] ... ob_digit[abs(ob_size)-1] are actually available.

CAUTION: Generic code manipulating subtypes of PyVarObject has to

aware that ints abuse ob_size's sign bit.

*/

So the number 23479521057823154763809 will be stored as:

+-----------------+------------------------+------------+

| index | 0 | 1 | 2 |

+-----------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| ob_digit[index] | 219150369 | 255756550 | 20365 |

+-----------------+-----------+------------+------------+

| ob_size | 3 |

+-----------------+------------------------+

219150369 _ 230 _ 0 + 255756550 _ 230 _ 1 + 20365 _ 230 _ 2 = 23479521057823154763809

- Floating Point: it is a variable whose value is a real number, stored as an approximate value in the form of a triplet (s, m, e) where s is the sign in {-1,1}, m mantissa and e exponent. Such a triplet represents the decimal number smb^e in scientific notation where b is the base of representation, namely: 2 on the computers. By varying e, we make the decimal point “float”. The real numbers are stored in Python according to the double precision format specified by the IEEE 754 standard. Thus, the sign is coded on 1 bit, the exponent on 11 bit and the 52-bit mantissa , 11 + 1 + 52 = 64 bits; the precision being 52 bits, thus 15 significant digits.

Number = ± mantissaexponent base

|-63-|62-----------52|51------------------------0|

|sign|---exponent----|---------mantissa----------|

|1bit|----11bits-----|----------52bits-----------|

To find information about float numbers used in python, you can use the command sys.float_info like the following:

>>> import sys

>>> sys.float_info

sys.float_info(max=1.7976931348623157e+308, max_exp=1024, max_10_exp=308, min=2.2250738585072014e-308,

min_exp=-1021, min_10_exp=-307, dig=15, mant_dig=53, epsilon=2.220446049250313e-16, radix=2, rounds=1)

Where :

- max: maximum representable number;

- max_exp: maximum degree base 2 (11 bits for the exponent ==> 2(11-1) = 1024);

- max_10_exp: maximum number e such that 10e is in [min , max];

- min: minimum representable number;

- min_exp: minimum degree 2;

- min_10_exp: minimum number e such that 10e is in [min , max];

- dig: maximum number of digits that can accurately display a number;

- mant_dig: maximum number of digits in the radix number system, which can accurately display a number(53 = 52 mant + 1 sign );

- epsilon: difference between 1 and the smallest number that is greater than 1 which can be represented as a floating point number;

- radix: base of the number system used;

- rounds: integer constant defining the rounding mode.

>>> import math

>>> math.pow(10.0,308) # max_10_exp=308

1e+308

>>> math.pow(10.0,309)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

OverflowError: math range error

>>> pow(10.0,309)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

OverflowError: (34, 'Numerical result out of range')

>>> 10.0e309

inf

>>> 10.0**309

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

OverflowError: (34, 'Numerical result out of range')

>>> 10.0e309 + 10.0e309 # sum of two infinite is infinit;

inf

>>> 10.0e309 - 10.0e309 # sub of two infinite is not a number(nan);

nan

>>> pow(10.0,-323)

1e-323

>>> pow(10.0,-324) # idk why, it should be -308 since min_10_exp=-307;

0.0

>>> f'{0.2 + 0.2 + 0.2 - 0.6:.55f}'

'0.0000000000000001110223024625156540423631668090820312500'

>>> 0.2 + 0.2 + 0.2 == 0.6

False

>>> 0.2 + 0.2 + 0.2

0.6000000000000001

>>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1

0.6

So as you can it is not recommended to accurately compare float numbers, even if they are equal for you, their representations may differ if the numbers are obtained in different ways.

>>> x = 1/3

>>> x.as_integer_ratio() # get the exact representation of the float x.

(6004799503160661, 18014398509481984) # so x = 6004799503160661 / 18014398509481984

>>> x == 6004799503160661/18014398509481984

True

Let’s see how computer represents 0.2:

# the closest value to 0.2 is equal to J/2**N where 2 / 10 ~= J / (2**N) ==> J ~= 2**N / 5

>>> 2**52 <= 2**55 // 5 < 2**53 # by trial and error N = 55

True

>>> q, r = divmod(2**55, 5) #

>>> r

3 # < 2.5 ==> Since the remainder is more than half of 5, the best approximation is obtained by rounding up:

>>> q + 1

7205759403792794

>>> 7205759403792794 * 10 ** 55 // 2 ** 55 # Discard the fractional part.

2000000000000000111022302462515654042363166809082031250 # the exact number stored in the computer which is the closest

#to 0.2 is 0.2000000000000000111022302462515654042363166809082031250

# Lets verify the result

>>> f'{0.2:.55f}'

'0.2000000000000000111022302462515654042363166809082031250'

For more information about Representation Error of floats, you can checkout Pythom Docs.

- Imaginary: Complex data type, corresponds to a variable whose value is a complex number, stored as a couple of floats (so in approximate value). The complex number 1 + 2i(math repr) is noted 1 + 2j, where the letter i is noted J.

>>> i = 1+2j

>>> type(i)

<class 'complex'>

>>> i.conjugate()

(1-2j)

>>> i.imag

2.0

>>> i.real

1.0

- Boolean: Boolean data type that can be True or False.

>>> a = True

>>> a

True

>>> not a

False

>>> type(a)

<class 'bool'>

>>> a.__int__()

1

>>> isinstance (a, int)

True

It should be noted that this data type(bool) is a subtype of int as the current example shows.

3.5 Sequences.

Go To TOC.

A sequence is a container of elements, indexed by numbers positive. These numbers vary from 0 to n-1 for a sequence containing n elements. The notation to refer to the ith element of the sequence is:

sequence[i-1] or sequence[-n+(i-1)]

To index the last element :

sequence[-1] or sequence[n-1]

To index the first element :

sequence[0] or sequence[-n]

you can extract a sequence from another sequence :

sequence0 = sequence[2:-2] equivalent to sequence[2:-2: 1]

sequencex = sequence[x:y:z]

where:

- x: the starting index(included);

- y: the ending index(excluded);

- z: the number of steps.

+----------+---+---+---+---+

| i | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | n = 4;

+----------+---+---+---+---+

| sequence | 3 | 8 | 9 | 9 | length = 4;

+----------+---+---+---+---+

| (+)index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | for i = 3; sequence[3-1] = sequence[-4+(3-1)];

+----------+---+---+---+---+

| (-)index |-4 |-3 |-2 |-1 | sequence[2] = sequence[-2] and this is True for 0 < i <= n;

+----------+---+---+---+---+

There are two types of sequences:

- Immutable sequences, which can no longer be modified after creation;

- Mutable sequences, which can be modified after creation;

The following table contains the common operations and methods for all sequences:

| operation/method | Description | Example(strings(Immutable),list(Mutable)) |

|---|---|---|

sequence[i], sequence[-n + i] |

return the element at index i. |

>>> string = "i am a string">>> string[2]‘a’ >>> string[-len(string) + 2]‘a’ |

sequence[i : j], sequence[-n + i : -n + j] |

slicing: extract a sequence from another sequence strating from index i(included) and ending at index j(excluded). |

>>> string[7:10]‘str’>>> string[-len(string) + 7:-len(string) + 10]‘str’ |

sequence[i : j : step_size], sequence[-n + i : -n + j: step_size], |

slicing: extract a sequence from another sequence strating from index i(included) and ending at index j(excluded) while iterating over the sequence with a step_size. |

>>> string[7:10:2]‘sr’ >>> string[-len(string) + 7:-len(string) + 10:2]‘sr’ |

sequence[i] = value, sequence[-n + i] = value |

assign a value to the sequence at index i. |

>> list0 = list('list')>>> list0[‘l’, ‘i’, ‘s’, ‘t’] >>> list0[1] = 'a'>>> list0[‘l’, ‘a’, ‘s’, ‘t’] >>> list0[-len(list0) + 1] = 'i'>>> list0[‘l’, ‘i’, ‘s’, ‘t’] |

sequence[i : j] = [values], sequence[-n + i : -n + j] = [values] |

slicing assignement: assign a slice of a sequence to [values] starting from index i(included) and ending at index j(excluded). |

>>> list0[1:3] = 1,2>>> list0[‘l’, 1, 2, ‘t’] >>> list0[-len(list0) + 1: -len(list0) + 3] = 'i','s'>>> list0[‘l’, ‘i’, ‘s’, ‘t’] |

sequence[i : j : step_size] = [values], sequence[-n + i : -n + j: step_size] = [values] |

slicing assignement: assign a slice of a sequence to [values] starting from index i(included) and ending at index j(excluded). with a step_size. |

>>> list0[0:3:2] = 1,2>>> list0[1, ‘i’, 2, ‘t’] >>> list0[-len(list0) : -len(list0) + 3: 2 ] = 'l','s'>>> list0[‘l’, ‘i’, ‘s’, ‘t’] |

del sequence[i], del sequence[i:j],del sequence[i:j:step_size] |

delete elements from sequence. | >>> del list0[1]>>> list0[‘l’, ‘s’, ‘t’] >>> del list0[0:3]>>> list0[] |

len(sequence) |

return the number of elements in the sequence. | >>> set0 = set([1,2,3])>>> tuple0 = (1,2,3)>>> list0 = ['s', 't', 'r']>>> string0 = 'str'>>> len(set0), len(tuple0), len(list0), len(string0)(3, 3, 3, 3) |

min(sequence), max(sequence) |

return the minimum and the maximum value in the sequence. | >>> min(set0), max(tuple0), min(list0), max(string0)(1, 3, ‘r’, ‘t’) |

sum(sequence) |

return the sum of values in the sequence. | >>> sum(set0), sum(tuple0)(6, 6) |

all(sequence), any(sequence) |

all return True if all elements in the sequence are True; any return True if at least one element in the sequence is True |

>>> list0 = [1,'2',1,[0,46,78]]>>> any(list0)True >>> all(list0)True >>> list0 = [1,'2',0,[1,46,78]]>>> all(list0)False >>> any(list0)True. |

3.5.1 Immutable Sequences.

Go To TOC.

Immutable sequences are objects whose values can no longer be changed after creation.

Those are :

- strings;

- tuples;

- bytes;

- frozenset.

3.5.1.1 Strings.

Go To TOC.

Strings are sequences of characters. A character is a value encoded on 8 bits;, to represent a value between 0 and 255. This corresponds to a sign of ASCII table (0 and 127) or extended table (128 to 255) for values higher.

Unlike other languages, there is no type specific Python for a character, and a character is nothing other than a string of length 1. There are, however, two character-specific primitives, which allow you to do the conversion between the character and its integer value: ord() and chr().

>>> chr(65),chr(90),chr(97),chr(122)

('A', 'Z', 'a', 'z')

>>> ord('A'),ord('Z'),ord('a'),ord('z')

(65, 90, 97, 122)

3.5.1.2 Tuples.

Go To TOC.

A tuple is basically an immutable list with a smaller size in memory.

>>> a = [1,2,3]

>>> b = (1,2,3)

>>> a.__sizeof__() # return the size in bytes

64

>>> b.__sizeof__()

48

A tuple can be used as dictionary keys and that’s not True for a list :

>>> notes = {('math','physics','biology'):85}

>>> colors

{('math','phisics','biology'):85}

>>> notes = {['math','phisics','biology']:85}

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unhashable type: 'list'

>>> a = tuple() # create an empty tuple using the built-in tuple () function.

>>> a = () # create an empty tuple using a tuple literal.

>>> a = ('string') # create a string not a tuple!!!!

>>> a

'string'

>>> type(a)

<class 'str'>

>>> a = ('string',) # If you want to create a tupe with one element, use the comma ',' .

>>> type(a)

<class 'tuple'>

>>> a

('string',)

>>> a = 'string', # It's all about the comma ','!!!!

>>> a

('string',)

>>> a = tuple("string") # using the built-in tuple() function.

>>> a

('s', 't', 'r', 'i', 'n', 'g')

3.5.1.3 Bytes.

Go To TOC.

Python allows you to handle integers from 0 to 127 corresponding to the ASCII table. It can be initialized by values in a sequence prefixed with b, or by a string of type str.

>>> byte0 = b'\x41' # hex value of the char 'A': string literal

>>> byte1 = b'A' # string literal

>>> byte2 = bytes('A', 'utf-8') # using the built-in function bytes()

>>> byte0, byte1, byte2

(b'A', b'A', b'A')

>>> type(byte0), type(byte1), type(byte2)

(<class 'bytes'>, <class 'bytes'>, <class 'bytes'>)

>>> id(byte0),id(byte1), id(byte2) # they reference the same object in memory !!!

(139812271740512, 139812271740512, 139812271740512)

>>> byte0[0], byte1[0], byte2[0] # same object in memory because their value is between -5 and 256 !!!

(65, 65, 65)

3.5.1.4 Frozenset.

Go To TOC.

The frozenset type is an immutable version of the set type. It is presented with the type set in the next section.

3.5.2 Mutable Sequences.

Go To TOC.

Mutable sequences implement a number of methods that allow you to add, remove or modify each of the elements that compose them.

Python offers several types of Mutable sequences:

- list;

- bytearray;

- set;

- array.

- Dictionary

3.5.2.1 List.

Go To TOC.

In a list, each item is separated by a comma, and the whole is surrounded by brackets.therefore, an empty list is written []. Lists are indexed by integers. Lists can be nested: list inside another list. Each item in the list can be of any data type.

The basic C structure of lists in Python (CPython) may look like this:

typedef struct {

PyObject_HEAD; // macro used for something similar to inheritance.

Py_ssize_t allocated; //amount of memory allocated

PyObject **items; //an array of pointers

} listiterobject;

Python allocates a space in memory to store this list, then allocates pointers to elements of the list. Therefore, a list in Python is an array of pointers.

For more information about object structures in python, you can refer to python doc.

There are multiple ways to create a list in Python. For example, you can create a list using literals or with the list built-in function :

>>> list0 = list ('list') # Using the built-in function list().

>>> list0

['l', 'i', 's', 't']

>>> list1 = ['l', 'i', 's', 't'] # Using the list literal.

>>> list0 == list1 # they share the same values.

True

>>> id(list0), id(list1)

(139976621720192, 139976622957824) # But they are different objects in memory.

>>> list2 = ['l', 'i', ['list'], 4,list0] # list can be nested(list inside a list).

>>> list0 in list2

True

>>> list2

['l', 'i', ['list'], 4, ['l', 'i', 's', 't']]

>>> len(list2)

5

>>> list2[1] = list1 # lists are mutable sequence

>>> list2

['l', ['l', 'i', 's', 't'], ['list'], 4, ['l', 'i', 's', 't']]

>>> list2[2:4] # return list2[2], list2[3].

[['listt'], 4]

>>> list2[1][:] # return second row with all columns.

['l', 'i', 's', 't']

>>> list2[1][:len(list2[:])] # same operation.

['l', 'i', 's', 't']

>>> del list2[1][:] # delete(dec refcount) all elements of the list(empty list).

>>> list2

['l', [], ['list'], 4, ['l', 'i', 's', 't']]

>>> del list2[1] # delete the second element of the list

>>> list2

['l', ['list'], 4, ['l', 'i', 's', 't']]

>>> list2[3][1] = list0

>>> list2

['l', ['list'], 4, ['l', ['l', 'i', 's', 't'], 's', 't']]

>>> list2[3][1][3]

't'

>>> copy = list2[ : ] # the interpreter create new list list2[:] and then name it copy(set the reference to it).

>>> id (copy), id(list2) # so they are not the same object;

(140274421284688, 140274420833168)

>>> copy1 = list2

>>> id (copy1) , id(list2) # so they are the same object;

(140274420833168, 140274420833168)

>>> list2 = list2 + [5] # the interpreter evaluate the right expression and create a new object.

>>> id(list2)

140274420932928

>>> list2 += ['1',2] # the interpreter in this statement doesn't create a new object since there are no operation at the right side of the equation.

>>> id(list2)

140274420932928

>>> list2.append(1) # same as before, the append() method operate on the same list.

>>> id(list2)

140274420932928

The table below groups together useful methods associated to lists :

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

list0.append(e) |

add the element e at the end of the list list0 while operating on the same list. |

>>> list0 = [1,2,3]>>> id(list0)140274420933408 >>> list0.append(4)>>> list0,id(list0)([1, 2, 3, 4], 140274420933408) |

list0.extend(list1) |

adds the elements of list1 at the end of the list list0 while operating on the same list. |

>>> list0.extend([5,6,7])>>> list0, id(list0)([1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7], 140274420933408) |

list0.insert(p,e) |

insert an element e at position p in the list0. |

>>> list0.insert(2,8)>>> id(list0)140274420933408 >>> list0[1, 2, 8, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] |

list0.remove(e) |

remove the first occurrence of e from the list. If no elements found, a ValueError exception will be raised. |

>>> list0.remove(8)>>> list0[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] >>> list0.remove(8)Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>ValueError: list.remove(x): x not in list |

list0.index(e,start,end) |

return the index of first occurrence of e in list0 starting from start to end. If the element is not in the list ==> raise a ValueError excepetion. |

>>> list0 = [1,2,5,6,8]>>> list0.index(5,1,4)2 >>> list0.index(5,6,4)Traceback (most recent call last): File <stdin>, line 1, in <module>ValueError: 5 is not in list |

list0.count(e) |

count the occurrence of e in list0 |

>>> list0.count(1)1 |

list0.sort(function,reverse) |

sort the items in the list. function and reverse are optional. It returns a None type. |

>>> list0 = [7,4,8,1,9,2]>>> list1 = list(list0)>>> list1.sort() >>> list1[1, 2, 4, 7, 8, 9] >>> list2 = list0>>> list2.sort(reverse=True)>>> list2[9, 8, 7, 4, 2, 1] |

list0.pop(index) |

removes and returns element at index index from the list. If index is not provided, the last item will be removed. |

>>> list2list0 = [7,4,8,1,9,2]>>> list0 = [7,4,8,1,9,2]>>> a = list0.pop()>>> a2 >>> list0[7, 4, 8, 1, 9] >>> list0.pop(2)8 |

list0.reverse() |

modify the list by reversing the order of the elements, and returns a None type. | >>> list0[7, 4, 1, 9] >>> list0.reverse()>>> list0[9, 1, 4, 7] |

list0.copy() |

create a new list object with the elements of list0 | >>> list0 = [1,2,3,4]>>> list1 = list0.copy()>>> list1[1, 2, 3, 4] >>> id(list0), id(list1)(140148949288192, 140148947950560) |

list0.clear() |

remove all the element in list0. | >>> list0.clear()>>> list0[] |

3.5.2.2 Bytearray.

Go To TOC.

The bytearray type is equivalent to the bytes type but it is mutuble instead. It implements some methods of the type str, such as startswith,endswith or find. It also allows to manipulate the data like a sequence, and implements some list methods, like append or pop.

>>> array = bytearray([71, 95 , 46])

>>> array

bytearray(b'G_.')

>>> array.startswith(b'G')

True

>>> array.endswith(b'_')

False

>>> array.find(b'_')

1

>>> array.index(b'_')

1

>>> array.append(123)

>>> array

bytearray(b'G_.{')

>>> array.pop()

123

>>> array[0] = 250

>>> array

bytearray(b'\xfa_.')

3.5.2.3 Set.

Go To TOC.

A set in python is a “container” containing non-repeating hashable elements in random order. Hashable elements are all objects of constant value. The hash method is used to return an error if the object does not have a constant value.

>>> a = { 'h', 'i', 't', 'h', 'e','r','e' } # set literal.

>>> a

{'t', 'i', 'r', 'e', 'h'}

>>> a = set('hithere') # built-in function set().

>>> a

{'t', 'i', 'r', 'e', 'h'}

>>> a = { i*i for i in range(20) if i%2 == 0} # set generator.

>>> a

{0, 64, 256, 4, 36, 100, 196, 324, 16, 144}

>>> a = {} # you can't create an empty set from literal.

>>> type(a)

<class 'dict'>

>>> hash('hithere') # unique value

1627860905157545572

>>> hash('hithere')

1627860905157545572

>>> hash('hithere')

1627860905157545572

>>> a.add('123') # sets are mutable.

>>> a

{'t', 'i', 'r', 'e', 'h', '123'}

To test if an element exists in a set, the hash of that element is computed, then compare that hash with the one that exists in a hash table. But iterating over a set is much slower as the example below shows:

>>> a = [ i*i for i in range(2000)]

>>> b = set(a)

>>> timeit.timeit("for i in a: pass", "from __main__ import a") # iterating over the list.

30.985541039000054

>>> timeit.timeit("for i in b: pass", "from __main__ import b") # iterating over the set is slower.

54.14052559299989

>>> timeit.timeit("if 10000 in a: pass", "from __main__ import a") # test if 10000 exists in the list.

2.3482788399996934

>>> timeit.timeit("if 10000 in b: pass", "from __main__ import b") # test if 10000 exists in the set is way much faster than a list.

0.08669805399995312

+--------------+-----------+------------+------------+------------+

| index | 0 | 1 | ... | 1999 |

+--------------+-----------+------------+------------+------------+ To chech if 10000 in the set a,

| elements | 0 | 1 | ... | 3996001 | the interpreter computes the hash

+--------------+-----------+------------+------------+------------+ of 10000 and compare to the existing

| hashes | h(0) | h(1) | ... | h(3996001) | hashes, if exists than stop.

+--------------+-----------+------------+------------+------------+

Frozenset is a set which is immutable and allows to freeze the contents of sequence and provide powerful and rapid new comparison methods.

>>> c = frozenset(a)

>>> timeit.timeit("if 10000 in c: pass", "from __main__ import c") # faster than a set.

0.07721891600067465

>>> b == c # same value.

True

>>> type(b) == type(c) # but not the same type.

False

Both types of sets share common methods:

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

set0.isdisjoint(set1) |

Returns True if set0 and set1 have no elements in common. |

>>> set0 = set('abcde')>>> set0{‘d’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> frozenset = set('fghij')>>> set1{‘h’, ‘j’, ‘g’, ‘f’, ‘i’} >>> set0.isdisjoint(set1)True |

set0.issubset(set1),set0 <= set1 |

Returns True if all elements of set0 belong to set1 |

>>> set2 = set('abc')>>> set2{‘b’, ‘a’, ‘c’} >>> set0.issubset(set2)False >>> set2.issubset(set0)True >>> set2 <= set0True |

set0.issuperset(set1), set0 >= set1 |

Returns True if all elements of set1 belong to set0 |

>>> set0.issuperset(set2)True >>> set2.issuperset(set0)False >>> set0 >= set2True |

set0.union(set1, ...), set0 \| set1 \|... |

Returns all items in set0 or set1 or … |

>>> set0.union(set1,set2){‘d’, ‘h’, ‘j’, ‘g’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’, ‘f’, ‘i’} >>> set0 \| set1 \| set2{‘d’, ‘h’, ‘j’, ‘g’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’, ‘f’, ‘i’} |

set0.intersection(set1, ...), set0 & set1 &... |

Returns all items that are in set0 and in set1 and in … |

>>> set0.intersection(set2){‘b’, ‘a’, ‘c’} |

set0.difference (set1, ...), set0 - set1 - ... |

Remove from set0 all common elements with set1, otherwise return set1 . |

>>> set0{‘d’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set2{‘b’, ‘a’, ‘c’} >>> set0{‘d’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set1{‘h’, ‘j’, ‘g’, ‘f’, ‘i’} >>> set2{‘b’, ‘a’, ‘c’} >>> set0 - set1{‘d’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0 - set2{‘d’, ‘e’} |

set0.symmetric_difference(set1, ...), set0 ^ set1 |

Returns all unique elements of both sets(union - intersection). | >>> set0{‘d’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set2{‘b’, ‘a’, ‘c’} >>> set0 ^ set2{‘d’, ‘e’}>>> (set0 | set2) - (set0 & set2){‘d’, ‘e’} |

set0.copy() |

Makes a copy of set0 into a new set object. |

>>> set1 = set0.copy()>>> id(set0), id(set1)(139623648877216, 139623649788704) |

Mutable sets additionally have the methods described in the following table:

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

set0.update (set1, ...), set0 \| = set1 \| ... |

Updates set0 with the union of set0 and set1 and … |

>>> set0 = set('abcd')>>> set1 = set('defg')>>> set0{‘b’, ‘a’, ‘d’, ‘c’} >>> set1{‘d’, ‘e’, ‘g’, ‘f’} >>> set0 \|= set1>>> set0{‘d’, ‘g’, ‘b’, ‘e’, ‘c’, ‘a’, ‘f’} |

set0.intersection_update(set1, ...), set0 & = set1 & ... |

Updates set0 with the intersection of set0 and set1 and … |

>>> set0 &= set1>>> set0{‘d’, ‘e’, ‘g’, ‘f’} |

set0.difference_update(set1, ...), set0 - = set1 \| ... |

Substract from set0 the shared elements with set1 and … |

>>> set0 = {'d', 'g', 'b', 'e', 'c', 'a', 'f'}>>> set1 = {'d', 'e', 'g', 'f'}>>> set0.difference_update(set1)>>> set0{‘b’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0 = {'d', 'g', 'b', 'e', 'c', 'a', 'f'}>>> set0 -= set1 \| {'a'}>>> set0{‘b’, ‘c’} |

set0.symmetric_difference_update(set1), set0 ^ = set1 |

return a set of elements that appear in one set but do not appear both sets. | >>> set0 = {'d', 'g', 'b', 'e', 'c', 'a', 'f'}>>> set0 ^= set1>>> set0{‘b’, ‘c’, ‘a’} |

set0.add(e) |

add an element to set0 |

>>> set0.add('d')>>> set0{‘b’, ‘d’, ‘c’, ‘a’} |

set0.remove(e) |

remove an element from set0 if exists, otherwise throw a KeyError exception. |

>>> set0.remove('d')>>> set0{‘b’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0.remove('d')Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>KeyError: ‘d’ |

set0.discard(e) |

Removes an element from the set. | >>> set0{‘b’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0.discard('b')>>> set0{‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0.discard('b')>>> set0{‘c’, ‘a’} |

set0.pop() |

removes an item from the set. | >>> set0 = {'d', 'g', 'b', 'e', 'c', 'a', 'f'}>>> set0.pop()‘b’ >>> set0{‘d’, ‘e’, ‘g’, ‘f’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0.pop()‘d’ >>> set0{‘e’, ‘g’, ‘f’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0.pop()‘e’ >>> set0{‘g’, ‘f’, ‘c’, ‘a’} >>> set0.pop()‘g’ |

set0.clear() |

remove all elements from the set. | >>> set0 = {'d', 'g', 'b', 'e', 'c', 'a', 'f'}>>> set0.clear()>>> set0set() |

For more information about sets and frozensets, you can refer to python docs.

3.5.2.4 Array.

Go To TOC.

An array is a 1-dimensional array with a limitation on the data type and size of each element. Arrays are more memory efficient. For more information about array, you can read python docs.

3.5.2.5 Dictionary.

Go To TOC.

Dictionary in python is unordered mutable collection of arbitrary key-value objects. it is sometimes also called associative array or hash table.

From cpython, you can find the implementation of dictionaries in c:

typedef struct {

/* Cached hash code of me_key. */

Py_hash_t me_hash; //cached hash code

PyObject *me_key; // a pointer to keys object;

PyObject *me_value; // a pointer to values object;

} PyDictKeyEntry;

So as you can see, dictionaries store pointers and not the values themselves. You can create a dictionary like the following :

>>> d = {'key1':'value1','key2':'value2'} # ceate a dictionary using literal

>>> d

{'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2'}

>>> d = dict(key1 = 'value1', key2 = 'value2') # using the built-in func

>>> d

{'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2'}

>>> d = dict([('key1', 'value1'),('key2', 'value2')]) # from list of tuples

>>> d

{'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2'}

>>> d = { 'key'+str(i) : 'value'+str(i) for i in range ( 4 )} # using generators

>>> d

{'key0': 'value0', 'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2', 'key3': 'value3'}

>>> d['key0'] = 'new_value' # dictionaries are mutable

>>> d

{'key0': 'new_value', 'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2', 'key3': 'value3'}

>>> d[0] = 1 # if key doesn't exist => create a new element in dict

>>> d

{'key0': 'new_value', 'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2', 'key3': 'value3', 0: 1}

The following table contains dictionary’s methods :

| Method | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

dict0.copy(), |

create a new copy of dict0. | >>> d1 = d.copy()>>> id(d1),id(d)(140526876838560, 140526876807808) |

dict.fromkeys(['key0','key1', ...], value) |

create a dictionary with the same value(None by default) for all keys. | >>> dict.fromkeys(['key0','key1']){‘key0’: None, ‘key1’: None} >>> dict.fromkeys(['key0','key1'],'value01'){‘key0’: ‘value01’, ‘key1’: ‘value01’} |

dict0.get(key0, ..., default ) |

returns the value of the dictionary at the specified key,but if it does not exist, it returns default (by default None). | >>> d.get('key0')‘new_value’ >>> d.get('key','no key match')‘no key match’ |

dict0.items() |

Returns (key, value) pairs as a dict_items type. | >>> d.items()dict_items([(‘key0’, ‘new_value’), (‘key1’, ‘value1’), (‘key2’, ‘value2’), (‘key3’, ‘value3’), (0, 1)]) |

dict0.key() |

Returns a list of keys. | d.keys()dict_keys([‘key0’, ‘key1’, ‘key2’, ‘key3’, 0]) |

dict0.values() |

Returns a list of values. | >>> d.values()dict_values([‘new_value’, ‘value1’, ‘value2’, ‘value3’, 1]) |

dict0.pop(key) |

removes the existing key and returns its value. | >>> d.pop('key0')‘new_value’ >>> d{‘key1’: ‘value1’, ‘key2’: ‘value2’, ‘key3’: ‘value3’, 0: 1}>>> d.pop('notexisted')Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>KeyError: ‘notexisted’ |

dict0.popitem() |

Removes a (key, value) pair from the dictionary and returns it as a tuple. LIFO(last in first out) | {‘key1’: ‘value1’, ‘key2’: ‘value2’, ‘key3’: ‘value3’}>>> d.popitem ()(‘key3’, ‘value3’) >>> d.popitem ()(‘key2’, ‘value2’) |

dict0.update([('key','value'),...]) |

updates the dictionary by adding the (key, value) pairs . Existing keys are overwritten. | >>> d = {'key0': 'new_value', 'key1': 'value1', 'key2': 'value2', 'key3': 'value3', 0: 1}>>> d.update([('key0','value0')])>>> d{‘key0’: ‘value0’, ‘key1’: ‘value1’, ‘key2’: ‘value2’, ‘key3’: ‘value3’, 0: 1} >>> d.update([('key4','value4')])>>> d{‘key0’: ‘value0’, ‘key1’: ‘value1’, ‘key2’: ‘value2’, ‘key3’: ‘value3’, 0: 1, ‘key4’: ‘value4’} |

3.5.3 Sequences Exercices.

Go To TOC.

>>> list_ = [1,2,3,4,5] # create a list from literal

>>> list_ +=6 # can't concatenate list and int

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'int' object is not iterable

>>> list_ +=[6]

>>> list_

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

>>> list_ +=(6,)

>>> list_

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6]

>>> list_ +=(6,7)

>>> list_

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 6, 7]

>>> list_[-1]

7

>>> list_.append(['a','b','c'])

>>> list_

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 6, 7, ['a', 'b', 'c']]

>>> list_.append('a','b','c')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: append() takes exactly one argument (3 given)

>>> del list_[-1]

>>> list_

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 6, 7]

>>> list_.extend(['a','b','c'])

>>> list_

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 6, 7, 'a', 'b', 'c']

>>> 'a' in list_

True

>>> not 'a' in list_

False

>>> 'a' not in list_

False

>>> ['a','b'] not in list_

True

>>> ('a','b') in list_

False

>>> *numbers, a, b, c = list_

>>> a

'a'

>>> b

'b'

>>> c

'c'

>>> numbers

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 6, 7]

>>> str_ = 'this is a string'.split()

>>> str_

['this', 'is', 'a', 'string']

>>> ','.join(str_)

'this,is,a,string'

>>> ','.join(str_)*2

'this,is,a,stringthis,is,a,string'

>>> str_.sort() # alphabetical sort and return None

>>> str_

['a', 'is', 'string', 'this']

>>> str_.reverse()

>>> str_

['this', 'string', 'is', 'a']

>>> str_.sort().reverse() # str_.sort() returns a None type.

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute 'reverse'

>>> a = sorted(numbers)

>>> a

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6, 6, 7]

>>> a = reversed(a) # return a generator

>>> a

<list_reverseiterator object at 0x7f901529ab10>

>>> a = list(a)

>>> a

[7, 6, 6, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1]

>>> days = ['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days[1]

'Tuesday'

>>> days[-1]

'Sunday'

>>> days[0:3]

['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday']

>>> days[0:-1]

['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday']

>>> days[0:]

['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days[0:1000]

['Monday', 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days2 = list(days)

>>> days3 = days.copy()

>>> days4 = days

>>> id(days),id(days2),id(days3),id(days4)

(140256807093424, 140256807093584, 140256807953344, 140256807093424)

>>> days2 is days

False

>>> days4 is days

True

>>> days[1:1] = [1,2] # that's kinda weird, it seems that it doen't check the upper slice

>>> days

['Monday', 1, 2, 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days[1:3] = [1,2]

>>> days

['Monday', 1, 2, 'Tuesday', 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days[1:4] = [1,2]

>>> days

['Monday', 1, 2, 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days[1] = [1,2]

>>> days

['Monday', [1, 2], 2, 'Wednesday', 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days[1:4:2] = [1,2]

>>> days

['Monday', 1, 2, 2, 'Thursday', 'Friday', 'Saturday', 'Sunday']

>>> days[1:1:2] = [1,2] # this error makes sense

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: attempt to assign sequence of size 2 to extended slice of size 1

>>> list(range(0,1000, 100))

[0, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900]

>>> list(range(1000, 0, -100))

[1000, 900, 800, 700, 600, 500, 400, 300, 200, 100]

>>> [i for i in range(20) if i % 2 == 0] # list comprehension, filter even numbers

[0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18]

>>> a = list(range(0,1000, 100))

>>> a[1:2] = [1,2]

>>> a

[0, 1, 2, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900]

>>> a = list(range(0,1000, 100))

>>> a[1:3] = [1,2]

>>> a

[0, 1, 2, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900]

>>> a[1:-1] = [1,2]

>>> a

[0, 1, 2, 900]

>>> a = list(range(0,1000, 100))

>>> a[1:-400] = [1,2]

>>> a

[0, 1, 2, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900]

>>> a[1:+400] = [1,2]

>>> a

[0, 1, 2]

>>> s1 = set(1, 2, 3)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: set expected at most 1 arguments, got 3

>>> s1 = set([1, 2, 3])

>>> s1

{1, 2, 3}

>>> s2 = set(range(1,7))

>>> s2

{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

>>> s1 < s2

True

>>> s1 <= s2

True

>>> s2 <= s2

True

>>> s2 < s2

False

>>> s2 -= s1

>>> s2

{4, 5, 6}

>>> s2 |= s1

>>> s2

{2, 1, 4, 5, 6, 3}

>>>

3.6 Conditional Statement.

Go To TOC.

These statements exists to allow you forcing the program to execute certain sections of code only under certain conditions. So if the condition is met, the code will be executed.

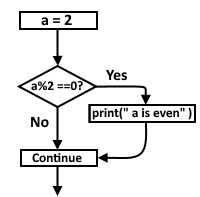

3.6.1 If Statement.

Go To TOC.

In this case, if the condition is met, then we go into the body of the indented block and execute the code in it. Otherwise, we skip this block and the program continue the excution normaly.

if <condition> :

....

....BLock of code

....

....

rest of program

a = 2

if a % 2 == 0:

print("a is even")

# continue

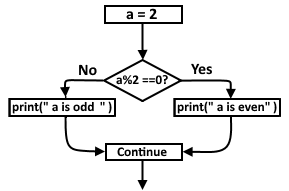

3.6.2 If-Else Statements.

Go To TOC.

Figuratively, we can divide this statement into two parts. The first part is an if statement with a condition and a body, and the second is an else statement with a body only.

a = 2

if a % 2 == 0:

print("a is even")

else:

print("a is odd")

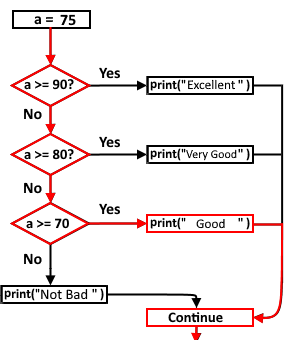

3.6.3 If-Elif Statements.

Go To TOC.

In this case, we only get into the body of the statement that the interpreter meets first, and as you may know, the interpreter scans the code from top to bottom(like switch-case in C# or C or …).

a = 75

if a >= 90:

print("Excellent")

elif a >= 80:

print("Very Good")

elif a <= 70:

print("Good")

else:

print("Not Bad")

# continue

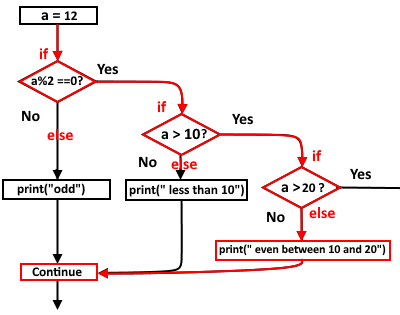

3.6.4 Nested If-Else Statements.

Go To TOC.

Here we check another condition if certain condition is met.

a = 12

if a%2 == 0:

if a > 10:

if a >20:

#code or another condition goes here

else :

print("even between 10 and 20")

else:

print("even less than 10")

else:

print("odd")

# Continue

The previous snippet of code is just a proof of concept on using the nested if-else and not a real example, I just used this example to demonstrate the mechanism of that conditional statement. In fact, you can rewrite the previous nested if-else conditionals into if-elif conditionals.

a = 12

if a%2 ==0 and a>10 and a <=20: # or if a%2 ==0 and 10 < a <=20:

print("even between 10 and 20")

elif a%2 == 0 and a <= 10:

print("even less than 10")

else:

print("odd")

3.6.5 Exercices.

Go To TOC.

>>> if []:

... print("True")

... else:

... print("False")

...

False

>>> bool([])

False

>>> bool(['1'])

True

>>> bool([None])

True

>>> bool('False')

True

>>> bool(True)

True

>>> bool(False)

False

>>> int(bool(False))

0

>>> int(bool(True))

1

>>> int(bool('False'))

1

>>> int(bool(None))

0

So in python, objects that hold content(values) are considered True(e.g. 1, [1,2,3], (0,), “Hello”,..), any other objects that doesn’t contain any value in it are considered False(e.g. [],(), ([]), None, 0, ““…). We can also say that if the len method(if the object has the attribute “__len__”) returns a value greater than or equal to 1, the truthiness of that object is considered True, otherwise it is False.

>>> bool([1])

True

>>> len([1])

1

>>> bool([])

False

>>> len([])

0

>>> bool([[]])

True

>>> len([[]])

1

>>> len([[[[]]]])

1

>>> bool(None)

False

>>> len(None)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: object of type 'NoneType' has no len()

>>> [].__len__()

0

>>> None.__len__()

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'NoneType' object has no attribute '__len__'

>>> bool([None])

True

>>> bool((None)) # this is not a typle because no comma in it !

False

>>> bool((None,)) # tuple contains something(Nonetype object)

True

3.7 Loops.

Go To TOC.

As said earlier, statements are executed sequentially from top to bottom. However, if you want to execute a block of code multiple times, you can use a loop.

But before diving in into loops, you need to have knowledge of some vocabulary:

- Iterable: In python, an iterable is an object that you can loop(iterate) over(e.g. list, dict, string…).

- Iteration: It is one excecution of the loop.

- Index: A variable used to keep track of the current iteration.

3.7.1 While Loop.

Go To TOC.

While loop means execute the body of this loop as long as the loop condition is true.

while condition:

body

>>> x = 10

>>> while x >= 0:

... print(x)

... x -= 1

...

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

So the interpreter first checks the condition if it is True or False, if True then executes the body statements, otherwise skip the body and continue with the rest of the program.

In python, you can also write an infinite loop. Using the break keyword, you can stop excecuting the body of the loop, or the continue keyword to skip the next iteration.

>>> while True:

... print(x)

... if x == 5:

... break

... else:

... x -= 1

... continue

... print("this statement will never be executed")

...

10

9

8

7

6

5

3.7.2 For Loop.

Go To TOC.

This loop iterates over any iterable object and executes the body of the loop during each iteration. For loops are much faster than while loops.

for variable_name in iterable:

body

>>> for x in range(10,-1,-1):

... print(x)

...

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

>>> timeit.timeit('x=10000\nwhile x>0: x-=1', number=10000)

9.10978822099969

>>> timeit.timeit('for x in range(10000,0,-1): x = x', number=10000) # for loops are much faster because of the range function.

4.98198106000018

3.7.3 Loop Else.

Go To TOC.

The else keyword is used, in a for or while loop, to check if the loop was exited nicely or something else interrupts its execution. if it exited nicely, the body of else statement will be executed.

>>> for i in range(5):

... print(i)

... else:

... print("Nothing interrupts the for loop!")

...

0

1

2

3

4

Nothing interrupts the for loop!

>>> for i in range(20):

... if i == 10:

... print("else will not be executed!")

... break

... else:

... print("else")

...

else will not be executed!

3.8 Operations.

Go To TOC.

In Python, operations have different priorities. The following table lists arithmetic and logical operations from highest to lowest priority:

| Operation | Description | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

() |

Parentheses. | >>> (2+1)*(3-1)6 |